When Newsweek's source admitted that he had misidentified the government document in which he had seen an account of Quran desecration at Guantánamo prison, Pentagon spokesman Lawrence Di Rita exploded, "People are dead because of what this son of a bitch said. How could he be credible now?"

Di Rita could have said the same things about his bosses in the Bush administration.

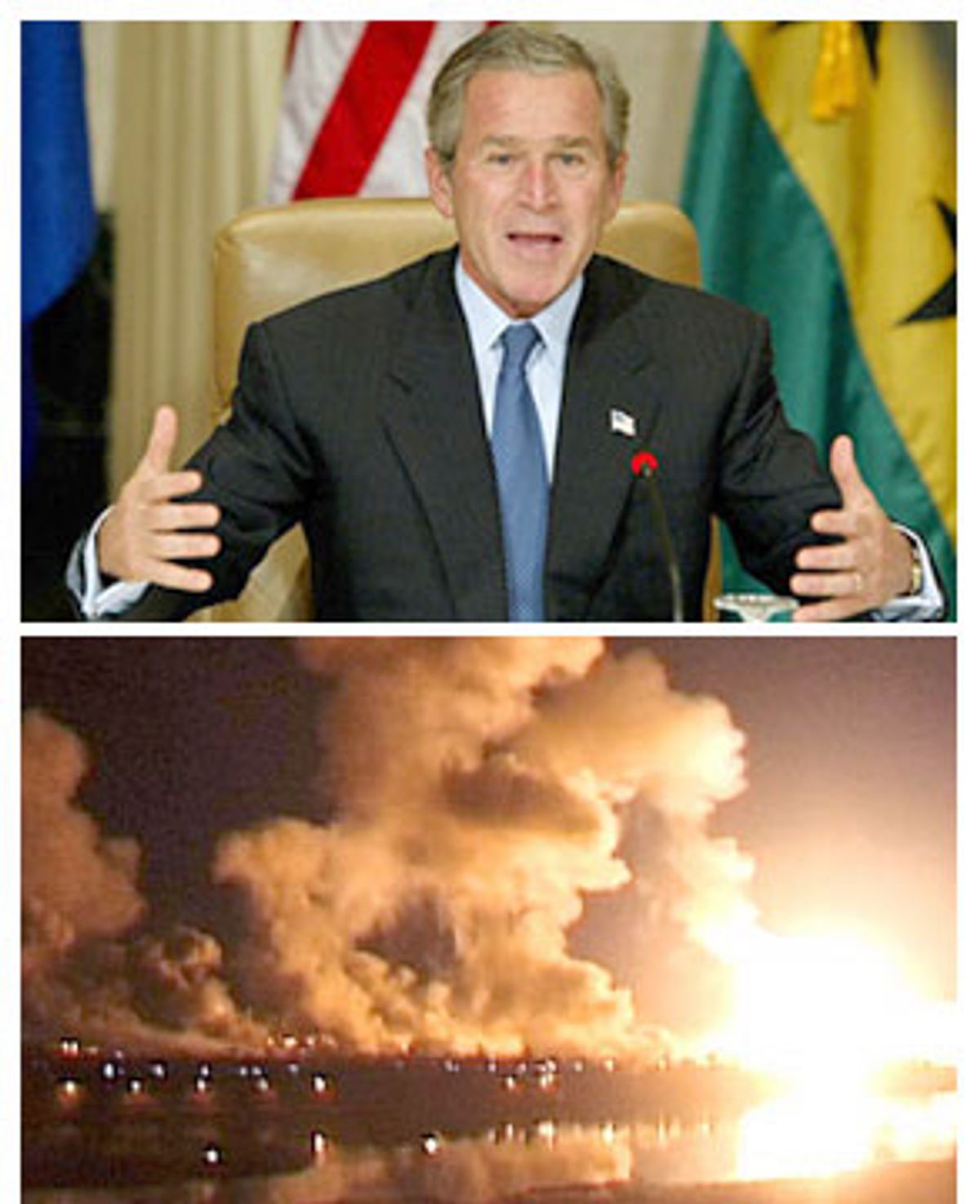

Tens of thousands of people are dead in Iraq, including more than 1,600 U.S. soldiers and Marines, because of false allegations made by President George W. Bush and Di Rita's more immediate boss, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, about Saddam Hussein's nonexistent weapons of mass destruction and equally imaginary active nuclear weapons program. Bush, Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice repeatedly made unfounded allegations that led to the continuing disaster in Iraq, much of which is now an economic and military no man's land beset by bombings, assassinations, kidnappings and political gridlock.

And we now know, thanks to a leaked British memo concerning the head of British intelligence, that the Bush administration -- contrary to its explicit denials -- had already made up its mind to attack Iraq and "fixed" those bogus allegations to support its decision. In short, Bush and his top officials lied about Iraq.

Going to war is the most serious decision a president can make. It should never be approached in a cavalier fashion. American lives, the prestige and influence of the country, international relations, the health of its defenses, and the future of the next generation are at stake. Yet every single piece of evidence we now have confirms that George W. Bush, who was obsessed with unseating Saddam Hussein even before 9/11, recklessly used the opportunity presented by the terror attacks to march the country to war, fixing the intelligence to justify his decision, and lying to the American people about the reasons for the war. In other times, this might have been an impeachable offense.

The media circus around the Newsweek story arrived in time to further divert attention from the explosive British memorandum. Although the leaked Downing Street memo, published by the London Times on May 1, revealed the deeply dishonest and manipulative way that the Bush administration took the United States (and the United Kingdom) to war against Iraq, the American press corps studiously ignored it for two weeks.

The memo reported a July 2002 meeting of key British Cabinet and other officials, held when Sir Richard Dearlove, head of the British intelligence service, MI6, returned from a trip to Washington. It revealed that the decision to go to war had already been made by that point: "Military action was now seen as inevitable," the notes by British national security aide Matthew Rycroft revealed. Dearlove reported, "Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy."

Members of the British Cabinet were worried by the news, the memo shows, since they knew that the case against Iraq was tissue-thin in international law and that there were several more egregious sinners in the weapons area than Iraq. Because the United Kingdom, unlike the United States, is a member of the International Criminal Court, its officials had to worry about being tried for war crimes if they became involved in an illegal war of aggression launched by Bush and lacking U.N. Security Council sanction. Prime Minister Tony Blair put his hopes in a ploy. He thought that Bush should arrange for the United Nations to demand a return to Iraq of weapons inspectors, with the hope that Saddam Hussein would refuse, thus creating a legal justification for war acceptable to the international community.

On May 6, Knight Ridder reporters Warren Strobel and John Walcott said that a former high official in the U.S. government told them that Dearlove's remarks were "an absolutely accurate description of what transpired" during his visit. This past Monday, White House spokesman Scott McClellan finally responded to the leaked document but denied that he had read it. Regarding the allegation that Bush fixed the intelligence around the Iraq war policy he said, "The suggestion is just flat-out wrong. Anyone who wants to know how the intelligence was used only has to go back and read everything that was said in public about the lead-up to the war."

It is hard to see how this absurdly vague methodology could actually refute the memo's charges or, indeed, to know what exactly McClellan was driving at. He added, "The president of the United States, in a very public way, reached out to people across the world, went to the United Nations, and tried to resolve this in a diplomatic manner." But as the memo makes clear, that "reaching out" was fraudulent, a smoke screen to cover a decision that had already been made. Bush went to the United Nations reluctantly and against the advice of the Cheney and Rumsfeld faction, mainly as a way of giving Saddam an ultimatum that would form the basis for a war.

The Bush administration, and some credulous or loyal members of the press, have long tried to blame U.S. intelligence services for exaggerating the Iraq threat and thus misleading the president into going to war. That position was always weak, and it is now revealed as laughable. President Bush was not misled by shoddy intelligence. Rather, he insisted on getting the intelligence that would support the war on which he had already decided. A good half of Americans, opinion polls show, now believe that the president actively lied to them about Iraq. In another, less cynical, flag-waving and intimidated age, this conclusion would provoke a scandal. The question would be, What did George W. Bush decide about Iraq, and when did he decide it?

The leaked British document demonstrates that the moment of decision was far earlier than the Bush administration publicly admitted. On Aug. 7, just weeks after the Dearlove visit to Washington, Cheney said in California that no decision had been made on Iraq. When Bush met with Saudi ambassador Bandar bin Sultan on Aug. 26, 2002, CNN reported that White House spokesman Ari Fleischer told the press, "The president stressed that he has made no decisions, that he will continue to engage in consultations with Saudi Arabia and other nations about steps in the Middle East, steps in Iraq." On Sept. 8, 2002, Cheney was interviewed by Tim Russert on "Meet the Press." Russert asked, "Will militarily this be a cakewalk? Two, how long would we be there and how much would it cost?" Cheney replied, "First of all, no decision's been made yet to launch a military operation."

The administration continued the charade that no decision had been taken through the end of 2002 and into 2003. In a White House press conference on Dec. 17, 2002, a questioner asked Fleischer, "The L.A. Times today published a poll that found that 72 percent of Americans, including 60 percent of Republicans, said the president has not provided enough evidence to justify starting a war with Iraq. Is the president losing the public relations battle here in the United States?"

"Well, one, I think that I'll just state what is well known," Fleischer replied. "The president will not make any decision about war and peace and the possibility of putting some of our nation's best men and women in harm's way on the basis of a poll. He will do it on the basis of his judgment as commander in chief and what it will take to save and protect American lives in the event that he reaches the conclusion Saddam Hussein will indeed engage in war against the United States or provide terrorists with weapons to engage in war against the United States, just like on September 11th with the attack. And if he reaches that judgment, he will do so because the information he has and the judgment he makes suggest that, not because of a poll."

The British memo is only the most decisive in a long list of documents that make it inescapably clear that Bush had decided to go to war long before. Indeed, Bush had decided as early as his presidential campaign in the year 2000 that he would find a way to fight an Iraq war to unseat Saddam. I was in the studio with Arab-American journalist Osama Siblani on Amy Goodman's "Democracy Now" program on March 11, 2005, when Siblani reported a May 2000 encounter he had with then-candidate Bush in a hotel in Troy, Mich. "He told me just straight to my face, among 12 or maybe 13 Republicans at that time here in Michigan at the hotel. I think it was on May 17, 2000, even before he became the nominee for the Republicans. He told me that he was going to take him out, when we talked about Saddam Hussein in Iraq." According to Siblani, Bush added that "he wanted to go to Iraq to search for weapons of mass destruction, and he considered the regime an imminent and gathering threat against the United States." Siblani points out that Bush at that point was privy to no classified intelligence on Iraqi weapons programs and had already made up his mind on the issue.

Siblani's account of Bush's stance is virtually identical to the impressions Dearlove brought back from Washington a little over two years later: "Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD." Iraq had long played the great white whale to W.'s Ahab, and the chance to move decisively against Saddam was intrinsic to his presidential ambitions.

Former Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill described to Ron Susskind in "The Price of Loyalty" the first Bush national security meeting of principals on Jan. 30, 2001. He writes that after Bush announced he would simply disengage from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and "unleash Sharon," he made it clear that Iraq would be a priority. "The hour almost up, Bush had assignments for everyone ... Rumsfeld and [Joint Chiefs chair Gen. H. Hugh] Shelton, he said, 'should examine our military options.' That included rebuilding the military coalition from the 1991 Gulf War, examining 'how it might look' to use U.S. ground forces in the north and the south of Iraq ... Ten days in, and it was about Iraq." Bush hit the ground running with regard to Iraq, shunting aside key U.S. foreign-policy goals -- such as a resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict -- in favor of exploring military options against Saddam Hussein. O'Neill reports a sense at the meeting that the reluctance to commit ground forces to an Asian war, a legacy of the Vietnam War, had ended with the advent of the Bush presidency.

An Iraq war might have been a hard sell, even for the skilled and highly manipulative Bush team. But Sept. 11 ensured that they could get congressional approval and public support for a war. Americans were angry and willing to lash out in any direction specified by the president. Former terrorism czar Richard Clarke related that on the evening of Sept. 12, 2001, Bush "grabbed a few of us and closed the door to the conference room. 'Look,' he told us, 'I know you have a lot to do and all ... but I want you, as soon as you can, to go back over everything, everything. See if Saddam did this. See if he's linked in any way...'" When Clarke protested that it was clearly an al-Qaida operation, Bush insisted, "Just look. I want to know any shred ... Look into Iraq, Saddam." According to Clarke, Bush said it "testily."

Clarke reveals that Rumsfeld was already, on the afternoon of Sept. 12, "talking about broadening the objectives of our response and 'getting Iraq.'" Although early accounts of National Security Council meetings after the attacks highlighted the role of Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz in pressing for an immediate war on Iraq, it has become increasingly clear that he was only one such voice, and hardly the most senior.

Astonishingly, the Bush administration almost took the United States to war against Iraq in the immediate aftermath of Sept. 11. We know about this episode from the public account of Sir Christopher Meyer, then the U.K. ambassador in Washington. Meyer reported that in the two weeks after Sept. 11, the Bush national security team argued back and forth over whether to attack Iraq or Afghanistan. It appears from his account that Bush was leaning toward the Iraq option.

Meyer spoke again about the matter to Vanity Fair for its May 2004 report, "The Path to War." Soon after Sept. 11, Meyer went to a dinner at the White House, "attended also by Colin Powell, [and] Condi Rice," where "Bush made clear that he was determined to topple Saddam. 'Rumors were already flying that Bush would use 9/11 as a pretext to attack Iraq,' Meyer remembers." When British Prime Minister Tony Blair arrived in Washington on Sept. 20, 2001, he was alarmed. If Blair had consulted MI6 about the relative merits of the Afghanistan and Iraq options, we can only imagine what well-informed British intelligence officers in Pakistan were cabling London about the dangers of leaving bin Laden and al-Qaida in place while plunging into a potential quagmire in Iraq. Fears that London was a major al-Qaida target would have underlined the risks to the United Kingdom of an "Iraq first" policy in Washington.

Meyer told Vanity Fair, "Blair came with a very strong message -- don't get distracted; the priorities were al-Qaida, Afghanistan, the Taliban." He must have been terrified that the Bush administration would abandon London to al-Qaida while pursuing the great white whale of Iraq. But he managed to help persuade Bush. Meyer reports, "Bush said, 'I agree with you, Tony. We must deal with this first. But when we have dealt with Afghanistan, we must come back to Iraq.'" Meyer also said, in spring 2004, that it was clear "that when we did come back to Iraq it wouldn't be to discuss smarter sanctions." In short, Meyer strongly implies that Blair persuaded Bush to make war on al-Qaida in Afghanistan first by promising him British support for a later Iraq campaign.

That the Afghanistan war went so well quickly enabled Bush to begin planning for an attack on Iraq. Bob Woodward reports in "Plan of Attack" that Bush asked Cheney for an Iraq war plan on Nov. 21. On Nov. 26 the Independent reported that Bush had called Saddam Hussein "evil" and demanded that he accept U.N. weapons inspectors. On Nov. 27 Howard Fineman of Newsweek reported a conversation with Bush aboard Air Force One in the wake of the successful Afghanistan campaign. "He wants to avoid the more profound mistakes his dad made...: his failure, at the end of the Gulf War, to stop -- once and for all -- Saddam Hussein in Iraq from threatening the world with weapons of mass destruction."

Nov. 27, 2001, was a significant date. Gen. Tommy Franks in his memoirs reveals that he received an unexpected call from Rumsfeld. "General Franks, the president wants us to look at options for Iraq." Franks knew exactly what the call portended. "Son of a bitch, I thought. No rest for the weary." There would be another war. The die had already been cast.

On Dec. 31 Newsweek reported, "In principle, Bush and his national-security team have decided that Saddam has to go, U.S. officials say. 'The question is not if the United States is going to hit Iraq; the question is when,' says a senior American envoy in the Middle East." The article notes Bush's oft-stated caution that no final decision had been made, but dismisses it on the basis of insider information. The main credit for this article was given to Christopher Dickey and John Barry, but Sami Kohen is listed as reporting from Turkey. Since a U.S. ambassador is quoted, and Kohen was the only one of the coauthors in the Middle East, he is likely the one who got the quote. Was his source Ambassador W. Robert Pearson?

Former Sen. Bob Graham of Florida says in his memoirs, "Intelligence Matters," that on Feb. 19, 2002, he visited the U.S. Central Command. Franks revealed to him that the command was no longer engaged in a war in Afghanistan. Graham was taken aback. Franks told the stunned senator, "Military and intelligence personnel are being re-deployed to prepare for an action in Iraq." The implementation phase had already begun.

In April 2002, Tony Blair went to see Bush at his Crawford, Texas, ranch. Vanity Fair reports that Blair stressed the need to get the backing of the United Nations for an Iraq war if he was going to swing Parliament behind it.

This long-term obsession of George W. Bush, then, was the background of the meeting in Washington with Dearlove in July 2002. Although Dearlove reported on a change of mood, such that the Iraq war was now a sure thing, he was probably actually observing that Bush had moved it to the front burner. By late July or very early August 2002, according to Vanity Fair, Blair had called Bush. A senior White House official who saw the transcript remarked, "The way it read was that, come what may, Saddam was going to go; they said they were going forward, they were going to take out the regime, and they were doing the right thing." Blair, he said, did not need any convincing. Both Blair and Bush would go on telling the public for months afterward that no final decision had been made about going to war.

It was also in midsummer 2002 that Franks asked Rumsfeld for $750 million to begin making preparations in Kuwait toward an Iraq war. The request, reported in Woodward's "Plan of Attack," provoked a good deal of controversy. Many in Congress felt that no specific appropriation had been made for such preparations, and the money was essentially taken from Afghanistan appropriations without congressional approval.

From Bush's meeting in May 2000 with Osama Siblani and 12 Republicans in a hotel room in Troy, Mich., until July 2002, his obsession with attacking Iraq never wavered. His first national security meeting was all about Iraq. He seriously considered attacking Iraq before Afghanistan after Sept. 11, and Blair had to argue him into the Afghanistan war. He had Rumsfeld ask Gen. Franks for an Iraq war plan on Nov. 27, 2001. The sense that Dearlove had, that the die had been inexorably cast by July 2002, was entirely correct.

But it is no positive reflection on the head of MI6 that he had not been able to discern that the die had been cast long before. The Downing Street memo is remarkable only for the frankness with which it acknowledges the illegality of the planned war and Bush's policy of "fixing" the intelligence around the policy. That the decision was made first, and various pretexts advanced for it in the aftermath, is now clear to the public.

Why has there not been more outrage in the United States at these revelations? Many Americans may have chosen to overlook the lies and deceptions the Bush administration used to justify the war because they still believe the Iraq war might have made them at least somewhat safer. When they realize that this hope, too, is unfounded, and that in fact the war has greatly increased the threat of another terrorist attack on U.S. soil, their wrath may be visited on the president and the political party that has brought America the biggest foreign-policy disaster since Vietnam.

Shares